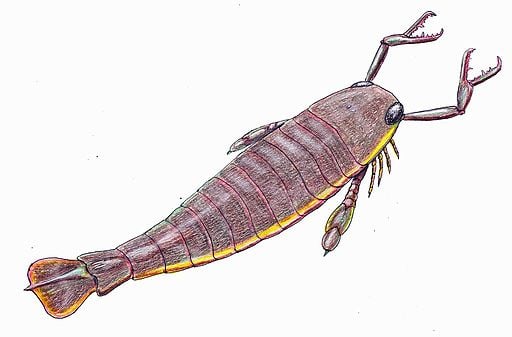

The Giant Sea Scorpion (Jaekelopterus rhenaniae) was one of the largest arthropods to ever exist, reaching lengths of up to 2.5 meters (8.2 feet). This massive predator dominated aquatic ecosystems during the Devonian period approximately 390 million years ago.

Despite its name, Jaekelopterus wasn't a true scorpion but rather a eurypterid - an extinct group of aquatic arthropods related to modern arachnids and horseshoe crabs. Fossil evidence suggests it was an apex predator that hunted fish, smaller arthropods, and possibly even early tetrapods.

The first fossils were discovered in Germany in 2007, with well-preserved chelicerae (claws) indicating this was one of the most formidable predators of its time. Its size likely gave it a significant advantage in capturing prey and competing with other predators.